Sermon for Sunday, July 12, 2015 || Proper 10B || Mark 6:14-29

I’ve never liked horror movies. I don’t understand the appeal of being scared out of my wits by things that go bump in the night or by gory chainsaw-driven bloodbaths. I don’t want to be afraid or disgusted, so why would I ever pay eleven dollars to subject myself to those emotions at the movie theater? I know that a lot of people out there enjoy horror movies, but if you’re anything like me in this regard, then the story I just finished reading possibly stirred in you the same feelings of fear and disgust that A Nightmare on Elm Street or Friday the Thirteenth might. The plot is truly dreadful: Herod throws a party to celebrate his birthday, but in the end, it is John the Baptizer’s death that is mourned. But even in the midst of these discomfiting emotions, I think we can still find something of value in this story.

I’ve never liked horror movies. I don’t understand the appeal of being scared out of my wits by things that go bump in the night or by gory chainsaw-driven bloodbaths. I don’t want to be afraid or disgusted, so why would I ever pay eleven dollars to subject myself to those emotions at the movie theater? I know that a lot of people out there enjoy horror movies, but if you’re anything like me in this regard, then the story I just finished reading possibly stirred in you the same feelings of fear and disgust that A Nightmare on Elm Street or Friday the Thirteenth might. The plot is truly dreadful: Herod throws a party to celebrate his birthday, but in the end, it is John the Baptizer’s death that is mourned. But even in the midst of these discomfiting emotions, I think we can still find something of value in this story.

To start, we must remember that Herod is a bad guy in the Gospel, so we shouldn’t be surprised that this flashback doesn’t end well. But we might be surprised that the story begins at least in shouting distance of the realm of good. Herod arrests John, it seems, for John’s own safety. We might call it “protective custody.” After all, Herod’s wife, Herodias, has a grudge against John and wants him dead. But Herod is intrigued by John. He thinks John has guts, and while what John says often bewilders Herod, the petty king likes having the prophet around.

Such is the status quo until Herod makes an ill-advised promise to his daughter (whose name is also Herodias, to make matters more confusing). “Whatever you ask me, I will give you, even half my kingdom,” Herod proclaims. The girl conspires with her mother and then asks for something really grisly: the head of John the Baptizer on a platter. What happens next is what I find especially interesting.

“The king was deeply grieved,” Mark narrates, “yet out of regard for his oaths and for the guests he did not want to refuse her.”

This is the moment of decision for Herod. I can hear in Herod’s mind, the petty king telling himself: “I have no choice. I don’t want John to die, but I gave my word!” However, Herod does have a choice. He can keep his promise or break it. Breaking a promise seems to me like a small price to pay to save a life, but Herod disagrees. He chooses to keep his word, despite the fact it means John will die. (Just so you know, for the sake of argument, I’m ignoring right now the fact that the promise Herod made was stupid and uninformed.)

Let’s dwell here for a few minutes and put ourselves in Herod’s shoes. Herod has a choice to make, and both options uphold a “good” of one type or another. Both can be defended as “right.” On the one hand, there is the good of keeping a promise. On the other, there is the good of saving someone’s life.

Now choosing between right and wrong is fairly easy in most cases. If you throw your baseball through the living room window just to see what breaking glass sounds like and then lie about it to your father, you’ve made two wrong choices. In general, if you have to keep your actions secret, you’ve done the wrong thing. So choosing between right and wrong is fairly easy. But choosing between right and right is much harder.

Here’s an example I used at a forum on this topic earlier this year. It’s 3 a.m. You’re on your way home from the airport, bone tired from a day of travel. You pull to a stop at a red light. No one’s coming. Do you run the light? Convenience may tell you to put the car in gear and keep on going. But, respect for the law keeps you waiting for the light to change. Here we have two goods in conflict, and I hope you’ll agree the good of respecting the law overrides the good of expediency.

Let’s add a wrinkle. It’s 3 a.m. Your wife’s contractions are only a few minutes apart. You hear her groaning and panting in the back seat. The baby is coming any minute now! You pull to a stop at a red light. No one’s coming. Now do you run the light? The good of respecting the law is in conflict with the good of protecting the safety of your family.

Choosing between right and right has a way of helping us clarify our values. Our values define us and guide us on the path of our moral lives. Each of us has a particular hierarchy of values instilled in us by our families and society at large, and our own life experience molds those values into certain shapes. Being followers of Jesus adds another dimension, as we seek to conform our values to the ones he displays in the Gospel. We’ll get to some of those in a minute, but first, we need to get back to Herod.

Herod has two goods in conflict: keeping a promise and saving a life. The narrator clues us in on Herod’s hierarchy of values: “Out of regard for his oaths and for the guests” he acquiesces to his daughter’s grisly appeal. For Herod, protecting John’s life ranks lower in his list of values than both upholding a promise and saving face. In the end, Herod cares much more about his own image than whether John lives or dies.

But remember, Herod is the bad guy. Let’s substitute Jesus in for Herod and see what happens to our hierarchy of values. While Herod was supremely concerned with his own image and standing, Jesus routinely ignored his image because rubbing shoulders with the least and the lost was more important to him. While Herod made outrageous oaths, Jesus said simply, “Let your ‘Yes’ be ‘Yes’ and your ‘No’ be ‘No.’ ” And while Herod was willing to let John die to save face, Jesus himself was willing to die to save us.

We can start to see Jesus’ hierarchy of values unfold here: Humble service over popular image. Simple honesty over dramatic protestations. Self-sacrifice over self-aggrandizement.

If we are paying attention, even just a little bit, during our day to day lives, we’ll start to notice how often we make choices between right and right. Do you read the whole book for class or do you take a break to keep from burning out? Do you work longer hours to put more money away for your kid’s college or do you make sure to see all your daughter’s dance recitals? Do you keep a friendship intact by not speaking up or do you risk the friendship by letting your friend know you’re concerned about his alcohol consumption?

If all our decisions were between what’s right and wrong, life would be so much easier. But that’s not the way it works. The path of our moral lives stretches before us. Our values are guideposts along the path. And Jesus is walking that path with us, pointing out which values he believes are most important. This sermon’s almost over, so I’m not going to tell you which values those are. Instead, I invite you to spend some time this summer reading the Gospel. Pick Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John – or read all four. They won’t take you too long. As you read the stories about Jesus, write down what he values. And ask yourself how his values fit into your hierarchy. What is his highest good? What is Jesus prompting you to shift around?

Twelve years ago today, I preached my very first sermon. Delivering a sermon was a requirement of my internship at St. Michael and All Angels Church in Dallas, Texas. So when the other four interns and I received the readings we’d all be preaching on, we dove right in, determined to preach the best sermons the great state of Texas had ever heard. That didn’t happen. But we each managed to say something coherent about Jesus calming the storm, and none of us fainted in the pulpit, so I call that a win. I have a muffled recording of the sermon I preached. I made the mistake of listening to it earlier this week. Wow, it’s really bad. There was something about complacency and faith and God shaking us up and Isaac Newton’s first law of motion, but I didn’t real say anything to take home with you.

Twelve years ago today, I preached my very first sermon. Delivering a sermon was a requirement of my internship at St. Michael and All Angels Church in Dallas, Texas. So when the other four interns and I received the readings we’d all be preaching on, we dove right in, determined to preach the best sermons the great state of Texas had ever heard. That didn’t happen. But we each managed to say something coherent about Jesus calming the storm, and none of us fainted in the pulpit, so I call that a win. I have a muffled recording of the sermon I preached. I made the mistake of listening to it earlier this week. Wow, it’s really bad. There was something about complacency and faith and God shaking us up and Isaac Newton’s first law of motion, but I didn’t real say anything to take home with you.

I first learned how to tell Godly Play stories back in 2006 when I was interning as a hospital chaplain at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, Texas. We chaplains had these miniature golden parable boxes, which we would bring to the patients’ rooms and lay out the stories on their beds. The first one I got my hands on comes from today’s Gospel lesson. The kingdom of God is “like a mustard seed, which, when sown upon the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on earth; yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes the greatest of all shrubs, and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.”

I first learned how to tell Godly Play stories back in 2006 when I was interning as a hospital chaplain at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, Texas. We chaplains had these miniature golden parable boxes, which we would bring to the patients’ rooms and lay out the stories on their beds. The first one I got my hands on comes from today’s Gospel lesson. The kingdom of God is “like a mustard seed, which, when sown upon the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on earth; yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes the greatest of all shrubs, and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.”

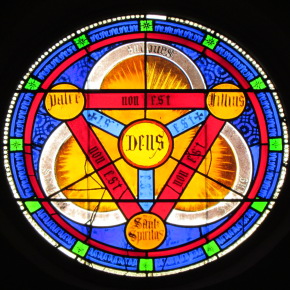

Have you ever looked closely at the round window high up the wall in the back of the church? Go ahead – turn around and give it a good look. I love this window. I love the vibrant colors. I love that when the sun is shining through it, an afterimage gets imprinted on my eyes, so I see it when I close them. If you’ve never given the window much thought, I don’t blame you. The words on it are in Latin, after all. But let’s keep looking. The window presents a diagram of the Holy Trinity. “Deus” – God – is encircled in the center. Three smaller circles float around it: Patri, Filius, Spiritus Sancti – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each of the smaller circles is connected to the others with the words “non est” (is not), and each smaller circle is connected to the large central one with the word “est” (is). The diagram is telling us that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not each other but they are all One God. How does this work? Wisely, the window doesn’t tell us. The window just illustrates the reality, a theological blueprint in stained glass.

Have you ever looked closely at the round window high up the wall in the back of the church? Go ahead – turn around and give it a good look. I love this window. I love the vibrant colors. I love that when the sun is shining through it, an afterimage gets imprinted on my eyes, so I see it when I close them. If you’ve never given the window much thought, I don’t blame you. The words on it are in Latin, after all. But let’s keep looking. The window presents a diagram of the Holy Trinity. “Deus” – God – is encircled in the center. Three smaller circles float around it: Patri, Filius, Spiritus Sancti – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each of the smaller circles is connected to the others with the words “non est” (is not), and each smaller circle is connected to the large central one with the word “est” (is). The diagram is telling us that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not each other but they are all One God. How does this work? Wisely, the window doesn’t tell us. The window just illustrates the reality, a theological blueprint in stained glass.

Stigma is not a happy word. If you use it in a sentence, more than likely the word “stigma” will be linked to something that people view as disgraceful or humiliating, whether that view is warranted or not. A couple of us recently read a book called The Rich and the Rest of Us by Tavis Smiley and Cornel West, who spoke of the need to lift the stigma associated with the word “poverty” if we are ever going to muster the societal will to lift those on the margins. In years past, society has stigmatized attributes of people who exhibit less capacity than most, using words like “retarded” and “crippled” to describe those with mental and physical challenges. Suffice to say that members of every minority group – no matter the difference used to justify labeling them as “those people” – have been stigmatized in one way or another. Stigmas lead to segregation and prejudicial behavior and animosity. “Stigma” is not a happy word.

Stigma is not a happy word. If you use it in a sentence, more than likely the word “stigma” will be linked to something that people view as disgraceful or humiliating, whether that view is warranted or not. A couple of us recently read a book called The Rich and the Rest of Us by Tavis Smiley and Cornel West, who spoke of the need to lift the stigma associated with the word “poverty” if we are ever going to muster the societal will to lift those on the margins. In years past, society has stigmatized attributes of people who exhibit less capacity than most, using words like “retarded” and “crippled” to describe those with mental and physical challenges. Suffice to say that members of every minority group – no matter the difference used to justify labeling them as “those people” – have been stigmatized in one way or another. Stigmas lead to segregation and prejudicial behavior and animosity. “Stigma” is not a happy word.

Good morning, and welcome to St. Mark’s on this glorious Easter Sunday. This morning we walk with Mary Magdalene to the tomb and find it empty. And yet our emptiness doesn’t last for long because Jesus, the Risen Christ, stands there, shining before us, as the dew glistens on the early spring flowers blossoming in the garden.

Good morning, and welcome to St. Mark’s on this glorious Easter Sunday. This morning we walk with Mary Magdalene to the tomb and find it empty. And yet our emptiness doesn’t last for long because Jesus, the Risen Christ, stands there, shining before us, as the dew glistens on the early spring flowers blossoming in the garden.

It’s great to have a baptism scheduled for the Easter Vigil, but we didn’t this year at St. Mark’s. I still wanted to bless the water of baptism before we renewed our baptismal covenant, so my father suggested I build the blessing into my sermon. At the vigil, you can preach before or after the transition from darkness to light, and this year I chose before.

It’s great to have a baptism scheduled for the Easter Vigil, but we didn’t this year at St. Mark’s. I still wanted to bless the water of baptism before we renewed our baptismal covenant, so my father suggested I build the blessing into my sermon. At the vigil, you can preach before or after the transition from darkness to light, and this year I chose before.

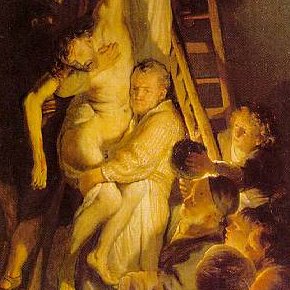

Imagine with me the thoughts of the Pharisee Nicodemus on his way home from helping Joseph of Arimathea bury the body of Jesus. Nicodemus appears at the end of the Passion Gospel reading, as well as two other places in the Gospel according to John, both of which are referenced in what follows.

Imagine with me the thoughts of the Pharisee Nicodemus on his way home from helping Joseph of Arimathea bury the body of Jesus. Nicodemus appears at the end of the Passion Gospel reading, as well as two other places in the Gospel according to John, both of which are referenced in what follows.

“Before the festival of the Passover, Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart from this world and go to the Father. Having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end.” Thus begins the second half of the Gospel according to John. We’ve walked with Jesus for three years since he called his first disciples, since he miraculously turned water into wine, since he drove the businesspeople out of the temple. We’ve overheard his conversations with the Pharisee Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman at the well. We’ve seen him heal a man suffering from paralysis and a man born blind. We’ve eaten the bread broken to feed 5,000 people. We’ve listened to Jesus call himself all sorts of names: the bread of life, the light of the world, the good shepherd. Recently, in an act that probably sealed his fate with his enemies, he raised his friend Lazarus from the dead.

“Before the festival of the Passover, Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart from this world and go to the Father. Having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end.” Thus begins the second half of the Gospel according to John. We’ve walked with Jesus for three years since he called his first disciples, since he miraculously turned water into wine, since he drove the businesspeople out of the temple. We’ve overheard his conversations with the Pharisee Nicodemus and the Samaritan woman at the well. We’ve seen him heal a man suffering from paralysis and a man born blind. We’ve eaten the bread broken to feed 5,000 people. We’ve listened to Jesus call himself all sorts of names: the bread of life, the light of the world, the good shepherd. Recently, in an act that probably sealed his fate with his enemies, he raised his friend Lazarus from the dead.