Sermon for Sunday, July 13, 2014 || Proper 10A || Matthew 13:1-9, 18-23

Okay, to start off: I’m not going to preach this morning about my rapidly approaching fatherhood. But I just want to point out God’s divine sense of humor in us reading in the Hebrew Scripture a story about the birth of twins. Rather, this morning, I’m going to preach about God’s persistence and God’s extravagance. To do this, I’d like to talk about the second of my three days of Godly Play training.

Okay, to start off: I’m not going to preach this morning about my rapidly approaching fatherhood. But I just want to point out God’s divine sense of humor in us reading in the Hebrew Scripture a story about the birth of twins. Rather, this morning, I’m going to preach about God’s persistence and God’s extravagance. To do this, I’d like to talk about the second of my three days of Godly Play training.

In Godly Play, Jesus’ parables reside in golden boxes, and on this second day of training, the leader invited the students to pair up and choose a box. Now, I don’t remember if I chose the parable of the sower or if the parable of the sower chose me, but either way, my partner and I opened our golden box to reveal a long piece of brown felt, three types of ground depicted on wooden cutouts, some tiny birds, and a sower with arm sweeping up from his satchel of grain.

We laid out the parable and started learning how to tell it in Godly Play style. We rolled out the long piece of felt underlay and slowly placed the types of ground on it. In Godly Play, everything happens slowly and deliberately. You take each piece out of the box, hold it, look at it, and draw the children into the story through your own focus and intentionality. Well, at that day of training, as I had just learned this theory, I was extra careful to move slowly, deliberately, and intentionally. I studied each piece as I removed it from the golden box. I held the sower. I held the birds. I held the rocky ground. I held the thorny soil. I held the good soil.

At the end of my first rehearsal of the story, all I could think was this: “Why waste so much seed?” Out of four types of ground, only one yielded grain. A mere 25 percent of the seed was successfully planted. The rest was stolen by birds or scorched in the sun or choked by thorns. What kind of sower would waste three-quarters of his seed?

Turns out, God is that kind of sower. Our God is a God of abundance, of surpassing love and extravagant grace. God scatters the seed of God’s word everywhere in creation and within the hearts of all people. What might seem like waste to us who are so often concerned with the scarcity of things, to God the scattering of seed among all things is simply standard operating procedure. The word of God is eternal. The word of God is never going to be exhausted. Thus, God can scatter as much of the seed of the word wherever God wants with no care given to it ever running out.

The prophet Isaiah proclaims such a reality when he speaks this word from God: “For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven, and do not return there until they have watered the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater, so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and succeed in the thing for which I sent it” (55:10-11).

So if God’s word accomplishes that for which God sent it, what of the seed that seems to be wasted? What of the seed that fell on the path, on the rocky ground, and among the thorns? These questions were on my mind as I continued preparing the parable of the sower for presentation at Godly Play training. But it wasn’t until I was putting away the parable for the final time that God gave me the gift of a small insight. I had already put the sower, the birds, and the types of ground back into the golden box. All that was left was the long strip of brown felt, the simple underlay for the other pieces. I sat there staring at it.

In a parable story, the felt underlay exists mostly to give shape to the other pieces. But as the first thing you pull from the golden box when you begin a story, the underlay can also serve as a warm-up activity to fire the imaginations of the children. “ ‘I wonder what this could be?’ you say,” as you turn the felt over in your hands, looking at both sides before smoothing it out on the floor. It’s a chocolate bar, a child might offer. It’s a brown snake. It’s a belt for a giant.

But as I sat there staring at the brown underlay all alone, I said, “I wonder what this could be?” and the answer came back, “It could be me.”

The brown felt upon which I placed the different kinds of ground could be any of – is each of us. Each of us, at various moments in our lives, has been the path upon which the birds came and ate. We have been the rocky ground. We have been the thorns. And hopefully, at some points, now or in the past or future, we have been the good soil. Thus, the kinds of ground upon which God’s seed falls are not different people, but different moments in the lives of each individual person.

Sometimes we receive the word with apathy and allow the birds to eat it up. Sometimes we dedicate ourselves with renewed fervor, only to have the fire burn hot and quick and die as soon as it started. Sometimes we allow the cares of the world to drown out the whispers of the abiding promises of God. And sometimes…sometimes we are receptive to God’s word, and the seed sprouts up abundantly.

I said at the beginning of this sermon that it would be about God’s persistence and God’s extravagance. Have you noticed them yet? The sower could plant the seed only in the good soil, but instead the sower flings it far and wide, trusting that even on challenging ground, the seed makes some impact. This is God’s extravagance – an expansive gesture of love and grace on the receptive and unreceptive alike.

And what of God’s persistence? Well, to extend the metaphor of the parable, the birds eat up the seed only to deposit it somewhere else. The seeds that die by scorching sun and choking thorn still sink into the loam to fertilize the ground. Thus, none of the seed is wasted; even the seed that falls outside the good soil can accomplish the purpose for which God cast it in the first place. Likewise, when you and I are at places in our lives when we are not exhibiting traits of good soil, God still casts seed upon us, knowing that even a hint of the word can make an impact, however small. Each seed cast upon us when we are unreceptive prepares us to become good soil at some future time. God yearns for us to be good soil, but God can wait because God is persistent.

As you take stock of your current relationship with God, ask God what kind of ground you are right now. What steps can you take to partner with God to till your soil into the kind receptive to God’s word? Trust that God continues to shower seed upon you because of God’s extravagant grace and persistent love no matter how many rocks or thorns stand in the way. The good news is this: sooner or later, in this life or the next, God’s word will take root in each of us because the sower will never run out of seed.

—

Sometimes when we pull a piece of the Gospel out of its natural habitat and read it in our cozy New England church, the impact of the words changes. Take the lesson I just finished, for example. How surprised would you be to learn that Jesus is trying to comfort his disciples with these words? You just heard them. They don’t sound very comforting, do they?

Sometimes when we pull a piece of the Gospel out of its natural habitat and read it in our cozy New England church, the impact of the words changes. Take the lesson I just finished, for example. How surprised would you be to learn that Jesus is trying to comfort his disciples with these words? You just heard them. They don’t sound very comforting, do they?

As most of you know, Leah and I are expecting twins in just a couple of weeks. I’ll let you in on a little secret. I am so excited. And terrified. And excited. Whenever I think of the immensity of the change that is about to take place in our lives, I get this “deer in the headlights” look on my face for a minute. But then I remember to breath, and I remember that we’re going to have a lot of help and support, and I remember what Jesus says at the end of today’s Gospel reading: “I am with you always.” And all that helps.

As most of you know, Leah and I are expecting twins in just a couple of weeks. I’ll let you in on a little secret. I am so excited. And terrified. And excited. Whenever I think of the immensity of the change that is about to take place in our lives, I get this “deer in the headlights” look on my face for a minute. But then I remember to breath, and I remember that we’re going to have a lot of help and support, and I remember what Jesus says at the end of today’s Gospel reading: “I am with you always.” And all that helps.

I couldn’t help but notice the readings selected for today all have some flavor of courtroom drama. We have the Apostle Paul sightseeing around Athens and discovering an out of the way shrine dedicated “to an unknown god.” When he stands up to debate at the Areopagus (the Athenian equivalent of the Supreme Court), he proclaims to the Athenians that this unknown god is the God who created all that is, the God of Abraham and his descendants, the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. At the end of his speech, some scoff at him and leave; others are intrigued and join Paul on his journey.

I couldn’t help but notice the readings selected for today all have some flavor of courtroom drama. We have the Apostle Paul sightseeing around Athens and discovering an out of the way shrine dedicated “to an unknown god.” When he stands up to debate at the Areopagus (the Athenian equivalent of the Supreme Court), he proclaims to the Athenians that this unknown god is the God who created all that is, the God of Abraham and his descendants, the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. At the end of his speech, some scoff at him and leave; others are intrigued and join Paul on his journey.

Attending seminary a few subway stops away from Washington D.C. provided some lovely distractions. The National Gallery of Art was my favorite. The Air and Space Museum was a close second. I visited most of the District’s tourist attractions during my three years there, and most lived up to their billing. One that did not was the D.C. zoo. The zoo is squashed into a tiny piece of the District, and the animals are squashed into tiny pieces of the zoo. The panda paddock was smaller than the backyard I mowed every week growing up. The elephants had no room to move. Everything was concrete and wrought iron. And the one time I went there, I couldn’t help but think what an inaccurate use of the word “zoo” I was witnessing.*

Attending seminary a few subway stops away from Washington D.C. provided some lovely distractions. The National Gallery of Art was my favorite. The Air and Space Museum was a close second. I visited most of the District’s tourist attractions during my three years there, and most lived up to their billing. One that did not was the D.C. zoo. The zoo is squashed into a tiny piece of the District, and the animals are squashed into tiny pieces of the zoo. The panda paddock was smaller than the backyard I mowed every week growing up. The elephants had no room to move. Everything was concrete and wrought iron. And the one time I went there, I couldn’t help but think what an inaccurate use of the word “zoo” I was witnessing.*

Today we are going on a journey to the center of a word. This word happens to be one of the most misused words in the English language, and it happens to be an important word in our Gospel lesson today. This word is “believe.”

Today we are going on a journey to the center of a word. This word happens to be one of the most misused words in the English language, and it happens to be an important word in our Gospel lesson today. This word is “believe.”

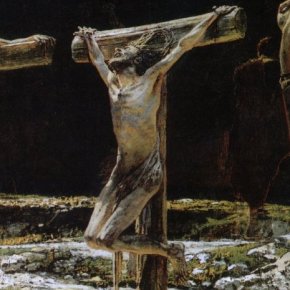

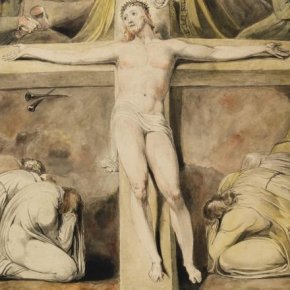

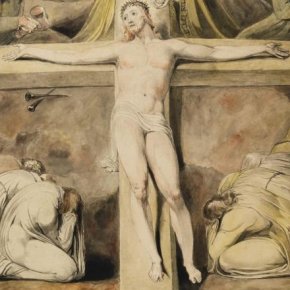

If you’ve spent any length of time in the Episcopal Church, you know the sermon comes after the Gospel reading. But because of the nature of our Gospel reading today, I hope you will allow me to flip that convention around. The Passion Gospel we will read in a few moments has the lyric substance of an epic poem; the depth of one of the works of a Russian master – Dostoyevsky, say; and the emotional weight of the entire book of Psalms: all in the space of an average magazine article. So rather than preaching after we listen to the performance of this momentous work of faith and story-telling, I thought I’d talk with you now, before we listen. I plan, in the next few minutes, to give you something of a listening guide: a few keys to listening faithfully, and a few things to listen for.

If you’ve spent any length of time in the Episcopal Church, you know the sermon comes after the Gospel reading. But because of the nature of our Gospel reading today, I hope you will allow me to flip that convention around. The Passion Gospel we will read in a few moments has the lyric substance of an epic poem; the depth of one of the works of a Russian master – Dostoyevsky, say; and the emotional weight of the entire book of Psalms: all in the space of an average magazine article. So rather than preaching after we listen to the performance of this momentous work of faith and story-telling, I thought I’d talk with you now, before we listen. I plan, in the next few minutes, to give you something of a listening guide: a few keys to listening faithfully, and a few things to listen for.