Sermon for Sunday, December 14, 2014 || Advent 3B || John 1:6-8, 19-28

Just before his death in 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus published his theory that corrected a long held belief about our planet’s place in the heavens. Initial curiosity by the establishment, including some power brokers of the Church, unfortunately succumbed to the prevailing wisdom of the day that the sun revolved around the earth and not the other way around. When Galileo picked up Copernicus’s theories a few decades later (and we must mention with less diplomatic tact than Copernicus had shown), Galileo was convicted of heresy, compelled to recant, and lived the rest of his life under house arrest. The heads of the Church could not handle this new information that implied we humans weren’t quite as special as they thought. Despite the definitive nature of Galileo’s proofs and despite further corroboration by other reputable scientists, the establishment for many years shut its collective eyes, covered its collective ears, and said, “We’re not listening!”

Just before his death in 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus published his theory that corrected a long held belief about our planet’s place in the heavens. Initial curiosity by the establishment, including some power brokers of the Church, unfortunately succumbed to the prevailing wisdom of the day that the sun revolved around the earth and not the other way around. When Galileo picked up Copernicus’s theories a few decades later (and we must mention with less diplomatic tact than Copernicus had shown), Galileo was convicted of heresy, compelled to recant, and lived the rest of his life under house arrest. The heads of the Church could not handle this new information that implied we humans weren’t quite as special as they thought. Despite the definitive nature of Galileo’s proofs and despite further corroboration by other reputable scientists, the establishment for many years shut its collective eyes, covered its collective ears, and said, “We’re not listening!”

Humans have always fallen victim to the particular notion that we each exist at the center of the universe. Just examine some common occurrences if you need evidence. When a young man of a certain disposition goes courting, an observer might say, “What does he think he is, God’s gift?” When doctors are accused of “playing God,” it’s often because their own egos have driven them to risky procedures. When the cult of celebrity that grips this country hails the triumphant return of a professional basketball player as the second coming or heeds the flawed advice of a low-wattage movie star concerning childhood vaccinations, then we’re all left to wonder why we don’t have such personal clout. And to top it off, how many of us have been told, when trying to insert ourselves into a friend’s troubles, “This isn’t about you!”

Thinking we are (or we should be) the center of the universe is just part of the human condition, but it’s a part of the human condition in continual need of rehabilitation. And in today’s Gospel reading, John the Baptist gives us a lesson. Recall that one of my favorite things about the Gospel is the fact that people rarely answer questions the way you expect them to. The priests and Levites come to John when he is baptizing in the Jordan and ask him a simple question: “Who are you?” Note how John could have answered as expected: “I’m John, son of Elizabeth and Zechariah, from down yonder a bit. Favorite pastime: baptizing with water. Likes include locusts and wild honey…”

But that’s not what John says. “Who are you?” they ask. And what does John do? He tells them who he is not. “I’m not the Messiah.” His rejection of messiah-hood throws his questioners for a loop and they start grasping at straws: “Are you Elijah? A prophet? Tell us who you are!” If a cult of celebrity exists today, then a similar one, albeit less fed by the fawning media, existed in John’s day. False messiahs cropped up all the time, attracted followers, and then lost them just as quickly when they couldn’t deliver the goods. That’s why, at the beginning of the Gospel, the establishment doesn’t much worry about Jesus. They assume he’s going to fade into obscurity like everyone else. Indeed, John’s denial of messiah-hood was much more newsworthy than claiming it would have been.

With John refusing the identities that the priests and Levites try to pin on him, they decide to ask him point blank: “What do you say about yourself?” They need an answer to bring to their superiors, but John never gives them satisfaction. Even when asked specifically about himself, John doesn’t take the bait. He deflects the attention from himself and shines it on the one who is to come, saying: “I am the voice of one crying out in the wilderness, ‘Make straight the way of the Lord.’ ”

John has no delusions of grandeur. He knows his place in the universe. He knows he is not the Messiah. And he also knows his relationship to the Messiah: “He himself was not the light, but he came to testify to the light.” John embraces an identity based in Jesus’ messiah-hood. John is the herald, the special voice that captures people’s attention and turns their eyes to the coming king. “What do you say about yourself?” they ask. And John responds: “My identity is based on the identity of the true Messiah. I am the voice, the herald, the witness. I am the arrow that always points to the one who is coming after me.”

John continues to display this identity throughout his short time in the Gospel. When his disciples see Jesus the next day, John the Arrow points and says, “Look, here is the Lamb of God!” He risks losing his own followers because he knows it is not his place to have followers. Later he repeats that he is not the Messiah, calling himself instead the “friend of the bridegroom.” John has now heard Jesus’ voice, so John proclaims: “My joy has been fulfilled. He must increase, but I must decrease.”

How in touch with his sense of self must John have been fully to embrace his identity as the arrow pointing to Jesus. How many of us would have felt jealous when our turn in the spotlight was over? How many of us would have tried to extend our fifteen minutes of fame? But not John. John knows he has no light of his own. He is the moon reflecting the light of the sun.

And so are we. The lesson we learn from John the Baptist today teaches us to delve within and discover our own true identities, the places in this universe where only you and I were made to fit. None of us was made to be the center of the universe, even if the human condition tries to trick us into believing that to be true. Our true identities are gifts from God; therefore, when you fully embrace your identity, when you try it on and it fits better than your favorite pair of jeans, then you will find yourself spontaneously pointing to the true center of the universe, the true light of the world.

Like John, we are arrows pointing to God. I invite you this week to list out all the different facets of your identity and pray about how each one connects back to the One who makes you who you are. Here’s a snippet of mine to get you started: I am a husband and a father. The love for my family that fuels these pieces of my identity comes directly from the love of God. I am a priest and a pastor. My service to God and others springs from the call Christ places on my heart. I am a singer and writer. My inspiration comes from the Holy Spirit’s creativity living within me.

As I continue to list out facets of my identity, I see this pattern continue: I am who I am because of God’s presence in my life. Claiming and proclaiming that presence makes me an arrow like John the Baptist. And not just me: each of us is an arrow pointing to God. Each of us is the moon reflecting the light of the sun.

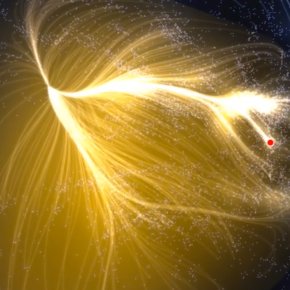

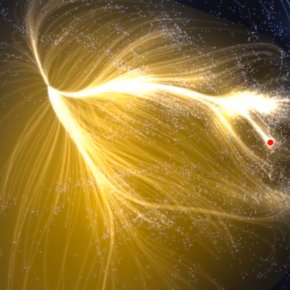

Copernicus and Galileo knew the earth wasn’t the center of the universe. But they had no idea how far away from it we actually are in space. Recent modeling shows our own solar system is tucked in a corner of the Milky Way galaxy and the Milky Way galaxy is tucked in a corner of a supercluster of galaxies known as Laniakea, and Laniakea is just one piece of a web of superclusters that make up the known universe. We might not be at the center of this universe, but the Creator of it is at the center of ours.

—

The Gospel writer Mark wastes no time telling us what his story is about. The very first words of his account of the Gospel proclaim without hesitation: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.” Matthew begins with a genealogy linking Jesus back to Abraham. Luke begins with a short address about his research methodology. John begins with a mysterious poem about creation. But Mark just hits the ground running and never looks back. “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”

The Gospel writer Mark wastes no time telling us what his story is about. The very first words of his account of the Gospel proclaim without hesitation: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.” Matthew begins with a genealogy linking Jesus back to Abraham. Luke begins with a short address about his research methodology. John begins with a mysterious poem about creation. But Mark just hits the ground running and never looks back. “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.”

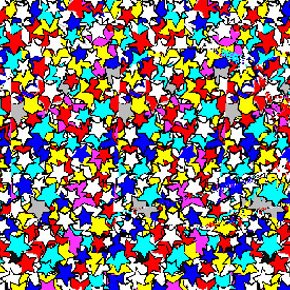

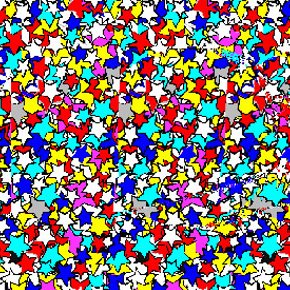

When I was a kid, there was a series of books called the Magic Eye books. Each page of these books was filled with what looked like very precise and geometric versions of Jackson Pollock’s art work. The pictures were just jumbles of kaleidoscopic lines and shapes, and if you didn’t know any better, that’s all you saw. But the trick with these books was that if you looked at the pictures a different way – sort of squint a bit – then you saw an image hiding beneath the jumbled surface picture. I’ll let you in on a little secret: I never once saw anything besides the geometric Jackson Pollock’s. No matter how often I lied to my friends and said, “Of course, I can see the person walking the dog,” I just could never get my eyes to focus correctly to see the hidden images. Let me tell you, it was quite frustrating.

When I was a kid, there was a series of books called the Magic Eye books. Each page of these books was filled with what looked like very precise and geometric versions of Jackson Pollock’s art work. The pictures were just jumbles of kaleidoscopic lines and shapes, and if you didn’t know any better, that’s all you saw. But the trick with these books was that if you looked at the pictures a different way – sort of squint a bit – then you saw an image hiding beneath the jumbled surface picture. I’ll let you in on a little secret: I never once saw anything besides the geometric Jackson Pollock’s. No matter how often I lied to my friends and said, “Of course, I can see the person walking the dog,” I just could never get my eyes to focus correctly to see the hidden images. Let me tell you, it was quite frustrating.

English is a strange language. We have thousands upon thousands of words – more than most languages – and more get added every year. And still there are plenty of instances in the English language where we employ the same word to speak about multiple concepts. I can’t bear to be in the same room as him. The apple trees are about to bear fruit. Yikes, there’s a bear in our campsite! Now bear with me. This idiosyncrasy of English often leads to confusion, especially among non-native speakers. What’s worse is that it can also lead to a concept being watered down, diluted when the various understandings of the word start to merge.

English is a strange language. We have thousands upon thousands of words – more than most languages – and more get added every year. And still there are plenty of instances in the English language where we employ the same word to speak about multiple concepts. I can’t bear to be in the same room as him. The apple trees are about to bear fruit. Yikes, there’s a bear in our campsite! Now bear with me. This idiosyncrasy of English often leads to confusion, especially among non-native speakers. What’s worse is that it can also lead to a concept being watered down, diluted when the various understandings of the word start to merge.

“Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Give to God the things that are God’s. Two weeks ago in the sermon and last week at the forum hour between services, we talked quite a bit about giving to God. We said that all giving to God is really and truly giving back to God. We said that good stewardship comprehends the intentional awareness that what we have isn’t really ours; therefore we cultivate an attitude in which all that we are and all that we have is a gift given back and forth between us and God.

“Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” Give to God the things that are God’s. Two weeks ago in the sermon and last week at the forum hour between services, we talked quite a bit about giving to God. We said that all giving to God is really and truly giving back to God. We said that good stewardship comprehends the intentional awareness that what we have isn’t really ours; therefore we cultivate an attitude in which all that we are and all that we have is a gift given back and forth between us and God.

My twins are not quite two months old, and yet I wonder when they will first look at the other and feel jealous. It might be my imagination, but I swear I’ve seen a barely perceptible glint in my daughter’s eye while she’s rocking away in the mechanical swing and I’m holding her brother – a barely perceptible glint of envy. Her eyes haven’t settled on a color yet, but I would swear in those few moments that they were green.

My twins are not quite two months old, and yet I wonder when they will first look at the other and feel jealous. It might be my imagination, but I swear I’ve seen a barely perceptible glint in my daughter’s eye while she’s rocking away in the mechanical swing and I’m holding her brother – a barely perceptible glint of envy. Her eyes haven’t settled on a color yet, but I would swear in those few moments that they were green.

“For when two or three are gathered together in my name, I am there among them.” I’ve always heard these famous words of Jesus as an astonishing promise, as a steadfast assurance that Christ is present in our midst no matter what. If you’ve ever been to a church gathering where only a few people showed up, I bet someone said, rather wistfully, “Well, when two or three are gathered…” I’ve said the same many times as a way to remind myself that what we’re doing when we gather as the church, as the body of those whose faith and action is motivated by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, is important, no matter the size of the group.

“For when two or three are gathered together in my name, I am there among them.” I’ve always heard these famous words of Jesus as an astonishing promise, as a steadfast assurance that Christ is present in our midst no matter what. If you’ve ever been to a church gathering where only a few people showed up, I bet someone said, rather wistfully, “Well, when two or three are gathered…” I’ve said the same many times as a way to remind myself that what we’re doing when we gather as the church, as the body of those whose faith and action is motivated by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, is important, no matter the size of the group.

For as long as I can remember, my father has worn a cross beneath his clothing, resting on his skin close to his heart. So when my parents gave me a cross of my own to wear when I was in my early teen years, I was thrilled. I was going to be just like Dad, wearing my cross all the time, even in the shower! The trouble was I kept losing it. I couldn’t wear the cross all the time because I played soccer, and there was a “no jewelry” rule. So it would get lost in the depths of my soccer bag (which was not a place for the faint of heart). The chain broke once, but I managed to find the cross beneath the seat of my car. Then during my freshman year of college the chain broke again, and I lost the cross for good.

For as long as I can remember, my father has worn a cross beneath his clothing, resting on his skin close to his heart. So when my parents gave me a cross of my own to wear when I was in my early teen years, I was thrilled. I was going to be just like Dad, wearing my cross all the time, even in the shower! The trouble was I kept losing it. I couldn’t wear the cross all the time because I played soccer, and there was a “no jewelry” rule. So it would get lost in the depths of my soccer bag (which was not a place for the faint of heart). The chain broke once, but I managed to find the cross beneath the seat of my car. Then during my freshman year of college the chain broke again, and I lost the cross for good.

Good morning! It’s good to be back after three weeks away. I know I’ve only been next door, but it seems like another world when newborns are filling all your waking (and the few sleeping) moments. I seriously thought about skipping this sermon entirely and just showing you baby pictures for the next ten minutes, but then I realized lemonade on the lawn might be a better venue for that. So, let’s get down to the sermon.

Good morning! It’s good to be back after three weeks away. I know I’ve only been next door, but it seems like another world when newborns are filling all your waking (and the few sleeping) moments. I seriously thought about skipping this sermon entirely and just showing you baby pictures for the next ten minutes, but then I realized lemonade on the lawn might be a better venue for that. So, let’s get down to the sermon.