During my sabbatical, I’m not writing new sermons, so on Mondays I am choosing one post from every year of WheretheWind.com to highlight. In 2015, I wrote this sermon for Trinity Sunday, and I really liked it.

Continue reading “Sabbatical Retrospective, Year 2015: The Blueprint”Tag: Trinity Sunday

Diversity Without Division, Unity Without Uniformity

Sermon for Sunday, June 11, 2017 || Trinity Sunday, Year A

If you look to the back of the church, you’ll notice we have a window missing right now. The good folks at Cathedral Stained Glass in New London are currently restoring our Trinity window, which has deteriorated over the years to the point where it could have shattered during a blustery storm. Today is not the most opportune Sunday of the church year to be lacking the Trinity window. Today is, after all, Trinity Sunday, and in years past I’ve enjoyed directing your attention to the window at the beginning of my sermons on this particular day. I can’t do that today. Instead, I can only direct your attention to the lack of the Trinity window.

But such a lack of the window stirs up some new thoughts; specifically the following question: Who would we be without the mystery and revelation of God as Trinity of Persons and Unity of Being? This question jumps to mind because, in recent years, many faithful Christians have wondered if we really need the encumbrance of the Trinitarian notion of God. Isn’t it just unnecessary baggage weighing down an already weighty topic, they argue. With fewer and fewer people finding God in the Christian church in the United States, wouldn’t it make sense to streamline our beliefs a little bit, make them easier to apprehend? Continue reading “Diversity Without Division, Unity Without Uniformity”

The Blueprint

Sermon for Sunday, May 31, 2015 || Trinity Sunday B

Have you ever looked closely at the round window high up the wall in the back of the church? Go ahead – turn around and give it a good look. I love this window. I love the vibrant colors. I love that when the sun is shining through it, an afterimage gets imprinted on my eyes, so I see it when I close them. If you’ve never given the window much thought, I don’t blame you. The words on it are in Latin, after all. But let’s keep looking. The window presents a diagram of the Holy Trinity. “Deus” – God – is encircled in the center. Three smaller circles float around it: Patri, Filius, Spiritus Sancti – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each of the smaller circles is connected to the others with the words “non est” (is not), and each smaller circle is connected to the large central one with the word “est” (is). The diagram is telling us that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not each other but they are all One God. How does this work? Wisely, the window doesn’t tell us. The window just illustrates the reality, a theological blueprint in stained glass.

Have you ever looked closely at the round window high up the wall in the back of the church? Go ahead – turn around and give it a good look. I love this window. I love the vibrant colors. I love that when the sun is shining through it, an afterimage gets imprinted on my eyes, so I see it when I close them. If you’ve never given the window much thought, I don’t blame you. The words on it are in Latin, after all. But let’s keep looking. The window presents a diagram of the Holy Trinity. “Deus” – God – is encircled in the center. Three smaller circles float around it: Patri, Filius, Spiritus Sancti – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Each of the smaller circles is connected to the others with the words “non est” (is not), and each smaller circle is connected to the large central one with the word “est” (is). The diagram is telling us that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are not each other but they are all One God. How does this work? Wisely, the window doesn’t tell us. The window just illustrates the reality, a theological blueprint in stained glass.

Likewise, I’m going to take my cue from the window and stay silent on the “How does this work?” question. Too many sermons over the years have tried to explain the mystery of the Trinity by talking about apples or flames. What those sermons didn’t understand is that you can’t explain a mystery without destroying the very quality that makes it mysterious. When Sherlock Holmes figures out that the bell rope used to call for the maid was replaced with a poisonous snake, which somehow slithered unnoticed out of the room in the ensuing hubbub over discovering the body, the mystery is solved. No more mystery. This Whodunnit? type mystery is the kind we’re used to: Gibbs and the NCIS team solve their mysteries within the length of the 45-minute episode. The light-hearted mystery novels my mother loves to read always wrap up the intrigue by the end of the story.

But here’s the difference between these small, ordinary mysteries we watch or read and the great mystery of the Holy Trinity. The small mysteries have answers to them, like the poisonous snake. But the mystery of the Holy Trinity is the answer – the fundamental answer that rests at the very core of existence. Here’s what I mean.

Before creation came into being, there was God. There was only God. Then God spoke, “Let there be light,” and creation erupted in a rush of dust and energy and far flung fire. And suddenly, there was something known as “not God.” Suddenly, there was an “other” for God to love. And yet, we believe that God’s essence is love, which means that God must have loved before there was a creation to love. Confusing, right? It is confusing until we realize there’s only one possible answer for whom God loved before there was anything else. God loved God. This may sound narcissistic or vain, but it’s not. Narcissism and vanity are distortions of love, but God’s love is perfect and unsullied. God loves God with such perfection that there is still only One God, even though a loving relationship exists.

That’s the keyword: relationship. To try to come close to the mystery of the Holy Trinity, we employ relational words: Father and Son, Parent and Child. We speak of the Holy Spirit as being the love that flows between them. This perfect relationship existed before creation, and thus serves as God’s blueprint for creation. Have you ever noticed that if you drill right down to the core of any subject whatsoever, you end up at relationship? At the most fundamental level, life, the universe, and everything are based on the relationships between things. Elemental particles vibrate next to other elemental particles, weaving the fabric of creation. Atoms repel and attract each other. Ecosystems thrive as complex series of relationships. Celestial bodies dance the precarious waltz of gravitational balance. Not to mention, the most important things in the lives of us humans on this fragile earth is our relationships with one another.

All of this grows from that blueprint God used from God’s own self – the perfect relationship of the Holy Trinity. In the act of creating something that was not God, God knew creation wouldn’t be perfect. And yet, God made it anyway. The reason the Holy Trinity remains a mystery is that our relationships – indeed, all relationships in creation – are not perfect, and thus we cannot fathom perfection.

But while we aren’t perfect, the idea of perfection lingers within us, an echo of our Creator’s own perfect love. We feel this echo as a longing for connection, for relationship with God and with each other. God loves us perfectly, even though we have the capacity to return a mere sliver of that love. But that sliver is more than enough to activate our ability to engage in loving relationships here and now. When we nurture such loving relationships in our lives, we come as close as our imperfection allows to the perfect relationship of the Holy Trinity.

Indeed, the Holy Trinity transcends our imperfection, draws us in, and strengthens our earthly relationships. The echo of God’s perfect love grows louder, more insistent, as we give ourselves over to be born again from above, to be remade closer to the blueprint than we were before. The blueprint calls for less domination and more mutuality, less prejudice and more generosity, less pride and more humility. The blueprint calls for less defending and more welcoming, less grasping and more embracing, less tearing down and more lifting up. And above all, the blueprint calls for love to spill forth in the forms of justice-seeking, mercy-granting, grace-sharing, hope-planting, and joy-singing.

And so you go home and do the dishes even though it was your brother’s turn. Or you tell your wife “thank you” for her poise in the middle of chaos and for putting up with you all these years. Or you introduce yourself to that bedraggled person you always seem to run into on your morning jog and ask if he needs assistance. Or you look those who are oppressed in the eye and say, “I’m sorry for not showing up sooner,” and then turn to stand with them.

Each of these is an expression of the blueprint of the perfect relationship of the Holy Trinity. And each of these will be done imperfectly. And yet, the mystery of the Holy Trinity rests at the core of all existence, of all we do and all we are. And so our imperfection is even now being redeemed by the perfect love of God, which somehow manages to fit all of itself into our mere slivers of love.

If in your life, the Holy Trinity has seemed no more than an abstraction, as clear as the Latin writing on the window back there, then I invite you to take a step back and look again. Reassign every single urge you have ever had to seek justice, to grant mercy, to share grace, to plant hope, to sing joy, and to love. Reassign all of them to the perfect love of the Trinity flowing, however imperfectly, through you. Notice now the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit catching you up in the ever-spinning dance of perfect love, and be thankful.

—

* The diagram of the Holy Trinity is the window on the back wall of St. Mark’s in Mystic, CT.

Whatever Passes Along the Paths of the Sea: The Oil Spill and Psalm 8

I first posted this reflection on Psalm 8 (the Psalm from Trinity Sunday) on the website Day1.org, a site on which I am a “key voices” blogger. If it sounds more academic than my normal writing, it is because this piece began it’s life as a seminary paper. I promise it sounds way more academic in it’s original version.

* * *

Seen from aerial photographs, the oil spill looks like any old gasoline rainbow you might see on the pavement outside a gas station after a drizzle. Then you realize the picture is taken from a few thousand feet and the patch of oil is hundreds of square miles in area and the spill is growing because it’s not a leak, it’s a geyser. Such thoughts send the mind reeling. How could we be so bold, so cocky, so derelict in our duty to God to be stewards of this creation that we pump toxic liquids out of the ground without so much as even a sketch of a plan to deal with the consequences of our own fallibility?

With these thoughts on my mind (and, I must confess, I am safely ensconced on a different coast far from the poisonous ooze), I glance at the readings for Trinity Sunday and the words of Psalm 8 hit me hard upside the head.

1. O LORD, our Sovereign,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!

You have set your glory above the heavens.

2. Out of the mouths of babes and infants

you have founded a bulwark because of your foes,

to silence the enemy and the avenger.

3. When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars that you have established;

4. what are human beings that you are mindful of them,

mortals that you care for them?

5. Yet you have made them a little lower than God,

and crowned them with glory and honor.

6. You have given them dominion over the works of your hands;

you have put all things under their feet,

7. all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field,

8. the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea,

whatever passes along the paths of the seas.

9. O LORD, our Sovereign,

how majestic is your name in all the earth!

With uncanny prescience, the psalmist speaks to our modern world about humanity’s role in creation, one based on the proper comprehension of humanity’s status as God’s subjects and therefore as servants of God’s creation. The second verse, which introduces the theme of dependence, seems out of place in the overarching language praising God for creation and humankind’s place in it. Of course, it’s always the verses that seem out of place that hold the most interpretive weight. By introducing the idea of dependence, the psalmist directs the audience to reflect on the necessity of human humility in regards to humanity’s relationship with God, especially concerning the dominion over creation.

At first glance verse 2 stands in contrast to the rest of the psalm since it concerns itself with enemies that are not mentioned again; further, verses 1 and 3 flow together nicely, with the thought of heaven connecting the two verses. But instead of mentally removing verse 2 so that the psalm flows smoothly, the reader must dwell on the second to come to the subtler and deeper orientation that the psalmist attempts to reach. The psalmist praises God for founding a “bulwark” (or strength, stronghold) against enemies “out of the mouths of babes and infants.” For those reading the psalms in order, this is the first time infants are mentioned in the entire Book of Psalms; indeed, the image of the babe is a fresh idea. A prevalent mental association made with infants is their dependency on their parents. The psalmist makes this association explicit by using not only the word for child, but also the word for “nursing infant,” The nursing infant truly is dependent on his or her mother in a way to which no other relationship quite compares. And it is out of the mouths of the utterly dependent that God achieves God’s plan — in this case beating back the foes, which scholar J. Clinton McCann deems “the chaotic forces that God conquered and ordered in the sovereign act of creation.”

With the interpretive key of dependence planted firmly in our minds, we can turn to the rest of the psalm. Verse 1 names God with the divine name and then follows with a title for God. The divine name automatically engenders feelings of obedience, but the addition of a title of “sovereign” serves as a further reminder that God is in charge. Because God exercises complete sovereignty, humans are as completely dependent on God as nursing infants are on their mothers.

Moving to verses 3-5, the psalmist looks up to the night sky and is walloped with a feeling of insignificance. And why not? In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams unwittingly offers an explanation of verse 3: “Space…is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly hugely mindbogglingly big it is. I mean you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.”

Scholar Peter Craigie points out that the psalmist drives home the point of humankind’s insignificance by saying that God establishes this mindbogglingly big thing with God’s fingers. This awareness of humanity’s smallness in the grand scheme could reduce us to apathetic movement through life because nothing we do would seem to matter. The psalmist nearly slips into this dangerous mode of thinking in v. 4; indeed, the hymn of praise could become a psalm lament at this point. But in the words “mortals that you care for them,” the reader recalls verse 2 and remembers that we are in a dependent relationship with God, who is our sovereign. Verse 5 continues this recollection by adding “yet you have made them (a little lower than God).” By reading verses 3-5 in light of verse 2, the faith that God made us and cares for us outweighs any feelings of insignificance that the night sky may provoke.

Verses 6-8 shift the focus from humankind’s dependence on God and humanity’s misplaced feelings of insignificance to the role God has ordained for humankind on earth. These verses recall the vocation God gives humanity on the sixth day of creation. While the word “dominion” in verse 6 is different than “dominion” in Genesis 1:26, the parallels with Genesis 1 are unmistakable. The language of largeness and smallness remains in these verses, which continues the theme of significance/insignificance seen in the previous three verses. God gives humankind dominion over small sheep, birds, and fish, and also large oxen, beasts, and “whatever passes along the paths of the seas” (the Leviathan which God “has made for the sport of it,” perhaps? (Psalm 104)). Humankind is given charge over great and small creatures; as the psalmist says, “you have put all things under their feet.” However, the psalm does not end with humanity’s dominion. In an inclusive bookend with verse 1, the psalmist reiterates the sovereignty of God over all things. This reprise recalls once again the dependence that humanity has on the LORD, who is their Lord.

What does this discussion offer the modern audience? We live in a global society hell-bent on destroying itself. We clear-cut forests, remove mountaintops, and pump toxic levels of Carbon Dioxide into the air. We do not share the bounty of the land, thus pushing others to burn rainforests and oases for farmland. We live under the delusion that we can develop “safe” oil rigs. We refuse to believe that our actions are slowly turning our world, a piece of God’s creation, into a planetary rubbish bin, fit only for storing the waste we accumulate.

Psalm 8 is a wakeup call, the An Inconvenient Truth of the Bible. To put it simply, the world today has forgotten the truth, which Psalm 8 espouses — that we are dependent on God even though (or more appropriately, especially because) we exercise dominion over the earth. We miss the all-important message that God has given us dominion: we do not intrinsically have it. We properly receive this gift only when we recognize our relationship with God is one of total dependence. Scholar James Mays puts it this way: Psalm 8’s “vision of the royal office of the human race is completely theocentric, but humanity in its career has performed the office in an anthropocentric mode. Dominion has become domination; rule has become ruin; subordination in the divine purpose has become subjection to human sinfulness.”

In the end, the problem is the oldest problem in the book — human self-aggrandizement destroys the purpose that God originally conceived for humanity. Misplaced delusions of grandeur unravel humanity’s proper relationship with God. Scholar Walter Brueggemann says, “Human persons are to rule, but they are not to receive the ultimate loyalty of creation. Such loyalty must be directed only to God.” Psalm 8 calls us back to the correct relationship with God concerning creation. We are utterly dependent on God, we are significant in the realm of creation, but we are not the source or the beginning (though we may very well be the end). In Psalm 8, the psalmist reclaims our primal orientation as dependent subjects on God who has been given us the gift of caring for creation. When we recover this proper relationship, we can take steps to retrieve creation from its slow decline, so that we can once again see the “majesty of God’s name in all the earth.”

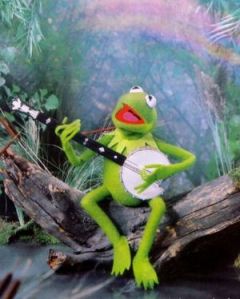

It’s not easy being green

The following post appeared Monday, May 3rd on Episcopalcafe.com, a website to which I am a monthly contributor. Check it out here or read it below.

* * *

Every February of my college years, the entire student body suffered from a mass case of seasonal affective disorder. The campus of Sewanee is one of the top five most beautiful spots on the planet, but the beauty of the Domain was difficult to appreciate during that dreadful month. What neophytes mistook for simple fog, veterans of Sewanee winters knew was in reality a low-hanging raincloud that hovered over the campus, sapping students of the will to do anything besides curl up under a blanket and nap. The weather lasted for weeks, and when the sun finally broke through the clinging barrier, we students discovered our vigor once again, as if by some sudden leap in evolution, we had developed the ability to photosynthesize.

Every February of my college years, the entire student body suffered from a mass case of seasonal affective disorder. The campus of Sewanee is one of the top five most beautiful spots on the planet, but the beauty of the Domain was difficult to appreciate during that dreadful month. What neophytes mistook for simple fog, veterans of Sewanee winters knew was in reality a low-hanging raincloud that hovered over the campus, sapping students of the will to do anything besides curl up under a blanket and nap. The weather lasted for weeks, and when the sun finally broke through the clinging barrier, we students discovered our vigor once again, as if by some sudden leap in evolution, we had developed the ability to photosynthesize.

A version of this same seasonal affective disorder hits Episcopalians every year within a few weeks of Pentecost. We look out over the vast expanse of the upcoming liturgical calendar, and we see nearly a month of Sundays with seemingly no variation, with nothing peculiar to distinguish one day from the next. It’s a sea of green, and without the concurrence of wedding season, the Altar Guild would forget where the paraments are stored.

We call it the season after Pentecost – even the designation gives it the sound of an afterthought. At first glance, those legendary church year framers seem to have measured the year wrong. They only programmed six months! What’s there to do with the rest, those twenty-odd Sundays after Pentecost that stretch on interminably during the dog days of summer and into the heart of autumn? Truly, we blanche at the long months and wonder if the Holy Spirit has enough juice in those Pentecost batteries to get us to the first Sunday of Advent.

The other liturgical seasons are nice and short; indeed, no other season creeps into double digits. Epiphany gets the closest, sometimes reaching as high as nine (watch out 2011!), but it can’t quite get there. And the short seasons always (and satisfyingly) lead somewhere: Advent moves to Christmas Day; Christmas season to the Epiphany; Epiphany season to Ash Wednesday; Lent to Easter Day; Easter season to Pentecost. Each season is like crossing a river or lake to the next feast or fast on the other side. But the season after Pentecost is an ocean, and Christ the King Sunday is in the next hemisphere.

So what do we do to combat the spiritual lethargy that can result from so many Sundays of unvarying green vestments? Well, we could try to split it into more liturgical seasons. So, starting with the Sunday after Pentecost, we’d have the season of the Trinity until mid-August. Then, beginning on August 15th, we’d have the season of the Blessed Virgin Mary until the end of September. Then, we’d have Michaelmas until Advent. There: three more manageable seasons for us modern people with our tweet-sized attention spans.

While this divvying up of the calendar has a certain appeal (especially to all the Anglo-Catholics reading this), I doubt the Church would go for it. So, where does that leave us? Our churches are still stuck in six months of monotonous green! The seasonal affective disorder will attack. Parishioners will fall away! (I know, I know – mostly because of summer holidays, but just go with me on this whole long liturgical season thing.)

Instead of lamenting the six months of green, let’s use the green season to our advantage. Don’t completely shut down program for the summer. Rather, take your cue from the liturgical color. Spend time each week or each month discussing how both the church and the individual can become more environmentally friendly. Devote education time to the intersection between theology and environmental sustainability. Set goals for the parish to meet by the end of the season after Pentecost to reduce consumption. Go paperless for the entire season to cut down on waste. Move service times to earlier in the day and turn off the A/C. Encourage people to bike to church or carpool. Have a light bulb changing party and replace all the lights with CFLs (the curlicue ones). Check out websites like nccecojustice.org for more ideas.

By taking positive steps to live into God’s pronouncement that we are stewards of creation and by staying active through the long days of the season after Pentecost, we can stave off that seasonal affective disorder. Even when the liturgical color hasn’t changed in four months, each Sunday is still a celebration of our Lord’s resurrection. Every Sunday we worship God, who through the Word brought all creation into being. The best way to praise God for that mighty creative act is by preserving it so countless generations to come can also praise God for God’s creation.

It’s a good thing the Green Season is so long. There sure is a lot to do.