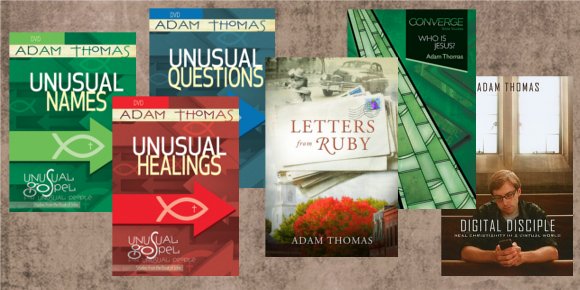

Since November 2009, I have been blessed to work with the good people at Abingdon Press to publish a variety of books and Bible studies. My first book, Digital Disciple, arrived in May 2011, and my most recent publication, Unusual Gospel for Unusual People, came out in April 2014. In between, I wrote the novel Letters from Ruby (August 2013) and contributed to the Converge series of Bible studies with Who is Jesus?

If you enjoy the content on this website and receive words of edification or encouragement from it, then I invite you to check out my published works. Here’s a quick overview of them, beginning with the most recent.

Unusual Gospel for Unusual People

It’s probably time for those of us who follow Jesus to realize we are once again the unusual ones in society. Sure, a majority of Americans profess a belief in God and identify as some sort of Christian, but there’s a big difference between checking “Christianity” on the census form and living your life as a follower of Jesus. People who strive to follow Jesus every day of their lives are fewer and farther between than at any point in history since the early church was still illegal. How many of us feel a bit weird talking about our faith in public? How many of us know the dialogue to old Friends episodes better than we know the stories that feed our faith? How many of us want to dedicate ourselves to Christ, but have trouble finding the time? If you’re like me, and you put yourselves in one or more of these categories, then the story you should read is this unusual Gospel of John.

It’s probably time for those of us who follow Jesus to realize we are once again the unusual ones in society. Sure, a majority of Americans profess a belief in God and identify as some sort of Christian, but there’s a big difference between checking “Christianity” on the census form and living your life as a follower of Jesus. People who strive to follow Jesus every day of their lives are fewer and farther between than at any point in history since the early church was still illegal. How many of us feel a bit weird talking about our faith in public? How many of us know the dialogue to old Friends episodes better than we know the stories that feed our faith? How many of us want to dedicate ourselves to Christ, but have trouble finding the time? If you’re like me, and you put yourselves in one or more of these categories, then the story you should read is this unusual Gospel of John.

The peculiar way John proclaims the good news of Jesus Christ speaks beautifully to our modern moment, especially to us unusual people. It probably hasn’t escaped your notice that it’s pretty different from Matthew, Mark, and Luke. It paints the same general picture, yes, but John uses different brushes, different techniques, and different colors than the others. There are no parables in John. Neither are there traditional healing stories nor demonic encounters nor transfiguration. The big moment in the upper room is washing the disciples’ feet, not offering them communion. Flipping over the moneychangers’ tables happens at the beginning, not the end. And Jesus never once keeps his divine identity a secret, as he does in the other three accounts. Let’s face it: John’s account of the Gospel is just plain unusual. Just like us.

Letters from Ruby

When the newly ordained Episcopal priest Rev. Calvin Harper arrives in Victory, West Virginia, to be the pastor at an ailing parish, he has no idea how much he still has to learn about being a priest. Thankfully, Ruby Redding takes the young man under her wing and teaches him everything she has learned throughout her long, storied life. Seminary never taught Calvin that the only true way to be a witness to God’s presence in this world is to remain in relationships with people no matter what life throws at them. His studies never taught him that detachment is the bane of ministry. He never learned that deep grief comes only from deep love. But in his first year in Victory, Calvin learns all this and more from Ruby, a woman so full of God’s light that it can’t help but spill onto the people around her.

When the newly ordained Episcopal priest Rev. Calvin Harper arrives in Victory, West Virginia, to be the pastor at an ailing parish, he has no idea how much he still has to learn about being a priest. Thankfully, Ruby Redding takes the young man under her wing and teaches him everything she has learned throughout her long, storied life. Seminary never taught Calvin that the only true way to be a witness to God’s presence in this world is to remain in relationships with people no matter what life throws at them. His studies never taught him that detachment is the bane of ministry. He never learned that deep grief comes only from deep love. But in his first year in Victory, Calvin learns all this and more from Ruby, a woman so full of God’s light that it can’t help but spill onto the people around her.

Converge: Who is Jesus?

Have you ever stopped to think just how much better Jesus Christ knows you than you know him? It’s a pretty staggering thought really. Not only that, Jesus knows you better than you know yourself. And although you’ll never know Jesus as well as he knows you, part of following the Son of God is getting to know him better. But you don’t want to fall into the trap of learning stuff “about” Jesus. Rather, you want to know Jesus himself. This study invites you to get to know four elements of what makes Jesus who he is: his name, his voice, his life, and his peace. In Who Is Jesus? you’ll discover that the more you know Jesus, the more Jesus will teach you who you are.

Have you ever stopped to think just how much better Jesus Christ knows you than you know him? It’s a pretty staggering thought really. Not only that, Jesus knows you better than you know yourself. And although you’ll never know Jesus as well as he knows you, part of following the Son of God is getting to know him better. But you don’t want to fall into the trap of learning stuff “about” Jesus. Rather, you want to know Jesus himself. This study invites you to get to know four elements of what makes Jesus who he is: his name, his voice, his life, and his peace. In Who Is Jesus? you’ll discover that the more you know Jesus, the more Jesus will teach you who you are.

Digital Disciple

This time in our society is unlike any other. People communicate daily without ever having to speak face to face, news breaks around the world in a matter of seconds, and favorite TV shows can be viewed at our convenience. We are, simultaneously, a people of connection and isolation. As Christians, how do we view our faith and personal ministry in this culture? Adam Thomas invites you to explore this question using his unique, personal, and often humorous insight. Thomas notes, “[The Internet] has added a new dimension to our lives; we are physical, emotional, spiritual, and now virtual people. But I believe that God continues to move through every facet of our existence, and that makes us new kinds of followers. We are digital disciples.”

This time in our society is unlike any other. People communicate daily without ever having to speak face to face, news breaks around the world in a matter of seconds, and favorite TV shows can be viewed at our convenience. We are, simultaneously, a people of connection and isolation. As Christians, how do we view our faith and personal ministry in this culture? Adam Thomas invites you to explore this question using his unique, personal, and often humorous insight. Thomas notes, “[The Internet] has added a new dimension to our lives; we are physical, emotional, spiritual, and now virtual people. But I believe that God continues to move through every facet of our existence, and that makes us new kinds of followers. We are digital disciples.”

—

Titles also available at your local bookstore or online at Amazon or Barnes and Noble. (But go to your local independent bookstore if you have one, because they are awesome.)

The viral papyri attributed to an associate of Jesus and espousing sound theological views eventually became what we now call the “New Testament.” The other stuff — the classified documents, location-specific texts, and the ones written by that guy — predictably faded into obscurity.*

The viral papyri attributed to an associate of Jesus and espousing sound theological views eventually became what we now call the “New Testament.” The other stuff — the classified documents, location-specific texts, and the ones written by that guy — predictably faded into obscurity.* and sever the connection between “evangelical” and “conservative” I’d never have to go back in time to make the attempt, thus the words would be connected, thus I’d go back in time and sever them, thus I’d not need to go back in time…you get the point. I’ve said it before — Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is the only book I’ve ever read with a truly well-reasoned time travel plot.)

and sever the connection between “evangelical” and “conservative” I’d never have to go back in time to make the attempt, thus the words would be connected, thus I’d go back in time and sever them, thus I’d not need to go back in time…you get the point. I’ve said it before — Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is the only book I’ve ever read with a truly well-reasoned time travel plot.) meone came up to me and said, “Who are you,” then responding, “Well, I’m not a toaster oven,” doesn’t really narrow it down.

meone came up to me and said, “Who are you,” then responding, “Well, I’m not a toaster oven,” doesn’t really narrow it down.