(Sermon for January 3, 2010 || Christmas 2, RCL || Luke 2:41-52)

They say that every therapist should be in therapy. Likewise, every priest should participate in spiritual direction. Without trained professionals helping us priests notice God’s movement in our lives, one of two things happens. We either forget to rely on God, thus emptying ourselves of all nourishment even though a feast is perpetually spread before us. Or we decide we don’t need to rely on God, because we are doing just fine on our own (thank you very much!) and the same starvation results. We priests are a rather thick bunch, usually quite stubborn when faced with the Almighty, because the Creator-of-All-That-Is rarely seems to fit the predictions of our seminary studies.

When I was in seminary, my spiritual director diagnosed my particular case as a combination of failing to notice God’s presence and deciding I didn’t need God anyway. I’m glad I could offer her such a potent mixture of blindness and stupidity. Needless to say, our sessions were never boring. Over our two years together, she taught me many things, but one stands above the rest. You can basically separate the events of your life into two categories, she said. There are moments of consolation, and there are moments of desolation. Both will happen and ignoring one will make the other that much harder to define. In this morning’s Gospel, Mary runs the gamut from desolation when she loses Jesus to consolation when she finds him again. Then she treasures “all these things in her heart” because she knows that the emptiness of desolation and the joy of consolation combine to form the trajectory of her life.

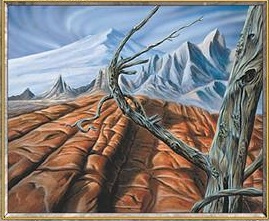

Usually, people want the bad news first, so we’ll begin with the emptiness of desolation. Desolation is the nuclear winter of the soul. Desolation makes the soul a wasteland – arid, parched, rendered uninhabitable by events in the life of the very person who must inhabit the internal desert.

Sometimes, we bring desolation on ourselves: a man cheats on his wife, and she doesn’t even catch him. He expects to feel the thrill of adventure, of subterfuge. Instead, he feels the pain of a broken promise. He doesn’t realize he is a moral person until he fails to live up to his own unexamined values. And his failure eats away at his soul. Sometimes, external events bring desolation upon us: the pregnancy has been difficult, but the doctors have managed to stay positive. If she can hold on just a few more weeks…but the contractions start, and she delivers a tiny life. The infant’s underdeveloped lungs struggle for breath. He lives for four days, and her soul dies with him. Sometimes, desolation happens not in these large events but in the accumulation of small frustrations and disappointments. They hired the other guy. The repair cost more than the estimate. Another D-minus. Chicken for dinner – again. Each frustration erodes the soil of the soul, nutrients leach out, and eventually only the wasteland remains.

In these times of desolation, we do not look for the presence of God because we think God can’t possibly be there. We abandon ourselves to despair, so we expect that God has abandoned us too. We may even stop believing in God, while paradoxically blaming God for our situations. When we are desolate, we don’t live: we merely subsist. And we fail to realize that our very ability to survive through the torment of despair is a manifestation of God’s awesome power and love.

While our desolation happens when we think God is gone, Mary’s desolate moment happens when she literally loses Jesus. The family has been attending the festival of the Passover in Jerusalem. They start their journey back to Nazareth, and Jesus is not with them. But they’re not worried because the caravan is peopled with family and friends; surely, he’s wandered off to chat with some favorite uncle. A day out, Mary and Joseph realize Jesus is missing. They rush back to Jerusalem, frightened, anxious. They search for three frantic days. As someone who has only experienced the combination of harsh words and fervent embraces that accompany a parent finding a lost child, I can only imagine the desolation that those three days brought to Mary’s soul.

On the third day, Mary’s search brings her to the temple. And there she finds Jesus, safe and sound and unaware of the years his absence has shaved off his mother’s life. Desolation gives way to the warmth, the electricity of consolation. What was lost, Mary now has found. They travel to Nazareth without incident, and Luke assures us that Jesus is obedient to his parents.

Whereas desolation makes the soul a wasteland, consolation makes the soul a garden in full bloom. In consolation, the roots of our souls grow deep in the rich soil of God’s presence. We are aware of the persistent activity of creation, and we revel in the joys that life has to offer.

Sometimes, our determination brings consolation to us: a young girl is told she’ll never become a concert pianist. Her hands are too small, her technique mediocre, pedestrian. But she practices and practices and practices. Her joy is in the vibration of hammer on string buzzing up through her fingertips, in the notes transferred from black dots and squiggles to tones of weight and beauty. She may never play at Carnegie Hall, but the music is inside her soul. Sometimes, as with desolation, external events bring consolation to us: the city-dweller finds himself in rural woodland at night. The sky is clear, the moon a sliver. He lies on his back and gazes up at the stars. He didn’t know there were so many. The subtle band of the Milky Way brings shape to the clutter. The innumerable points of light in the darkness bring light to his soul. More often than not, consolation happens when we gather together all of the small blessings in our lives. A good night’s sleep leads to energy and cheerfulness. An unexpected phone call comes from an old friend. The house is warm. Chicken for dinner again! Each blessing enriches the soil, in which our souls thrive, and our gardens bloom with unrestrained life.

In these times of consolation, we notice God filling us to overflowing. We cannot possibly hold any more grace, so it spills from us, hopefully landing on those around us. Our joy prompts us to invite others to gather up their blessings and notice God’s presence in their lives. We form communities to share our joy, and these communities help sustain those who inevitably fall into periods of desolation.

You see, desolation and consolation are the extremes of life – the subsistence and the abundance. Most of the time, we exist somewhere along the spectrum between the two. Luke tells us that Mary treasures “all these things in her heart” – both the empty time of desolation when Jesus was lost and the joyful time of consolation when she found him again. Mary takes both categories into her heart and ponders them. Her life, like all our lives, brings together experiences both of desolation and consolation. As faithful people of God, we try with God’s help to lead lives that trend toward consolation on the spectrum.

As we begin a new year and a new decade, I invite you to take stock of where you fall on the spectrum between desolation and consolation. If your trajectory is moving toward consolation, rejoice, and continue to gather your small blessings and keep a weather eye out for God’s presence in your life. If your trajectory is moving toward desolation, I pray that God grants you the courage to turn around. You may still be stuck in the wasteland, but you will be facing the right direction – out of the desert and toward the garden.

Finally, may God grant you the grace to survive when you are desolate, to thrive when you are overflowing, and to treasure all these things in your hearts.