Sermon for Sunday, January 4, 2026 || Christmas 2 || Matthew 2:13-15, (16-18), 19-23

In a 2003 song, the band Death Cab for Cutie sings, “So this is the new year / And I don’t feel any different.” That’s about how I feel today, and it’s not a great feeling. The new calendar on our kitchen wall features pictures of our kids and our nieces and nephews a year older than they were in last year’s calendar. But other than that, nothing has changed. The turn from December to January is symbolic only. Four days ago, we marked that the earth completed another revolution around the sun, but every day could mark the same. Indeed, other calendars set the date later this year: Chinese New Year is February 17th, Rosh Hashanah (Jewish New Year) is September 11th.

“So this is the new year / and I don’t feel any different.” I feel just as worn out as I did in 2025, just as exhausted by the constant crises and tragedies and atrocities, as well as the everyday injustices that affect so many people, both in our community and around the world. Because I am personally someone whose identity and position in our society means that my rights are fully recognized, I find it so so tempting just to check out, to hop in a bubble of privileged isolation until “better times” come. Apathy lures me, a siren song of indifferent bliss.

As I fight against this temptation, I realize why I’m so tired. I’m so tired because I’m fighting the temptation.1 If I gave in, if I let apathy dull me into the bliss of resignation, I would find a semblance of rest. But it would be an unquiet rest, like that of a ghost with unfinished business on earth. True restfulness cannot happen until we intersect our compassionate hearts with the axis of the world’s deepest hunger. Because only at this intersection are we able to live authentic lives of meaning and service. At the same time, we recognize that the world’s hunger is insatiable and our compassion is not everlasting. So we pray to God for the spring of grace to overflow with patience, perseverance, and courage. We pray to God for the daily renewal of our compassion so that we can remain present to the world’s hunger. We pray to God for the strength not to look away from suffering.

And that’s why I’m so disappointed today in the framers of our lectionary readings. Our Gospel lesson today skips the suffering in verses 16-18 of Matthew Chapter Two. They’re pretty important verses, but I suppose the framers decided that – at Christmastime – no one wants to think about slaughtering infants, so they jumped from Verse 15 to Verse 19. But in doing so, they have deprived us of a biblical encounter with atrocity that could, if we read it, help us confront similar atrocity in our modern world. An angel warns Joseph that Herod wants to kill Jesus, so the Holy Family flees to Egypt as refugees. Then we skipped three verses. Then Herod dies, and Joseph returns to Israel, but settles in Galilee, about as far from Herod’s successor as he can get and still be in Israel. Here are the verses we skipped:

When Herod saw that he had been tricked by the magi, he was infuriated, and he sent and killed all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had learned from the magi. Then what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah was fulfilled: “A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.”

Herod was a petty king, a tyrant drunk on the limited power he received from his Roman overlords. And when a petty king gets mad or afraid, he has enough power to lash out and destroy the lives of the vulnerable people under his rule. It was true in Moses’ day when Pharaoh slaughtered the Hebrew boys. It was true in Jesus’ day when Herod did the same to Bethlehem’s children. It remains true today. When we skip uncomfortable verses like these and sanitize the biblical witness, we never give ourselves the chance to confront our discomfort. And if we can’t confront this discomfort in the Bible, how could we ever confront the powers of our world committing similar atrocities?

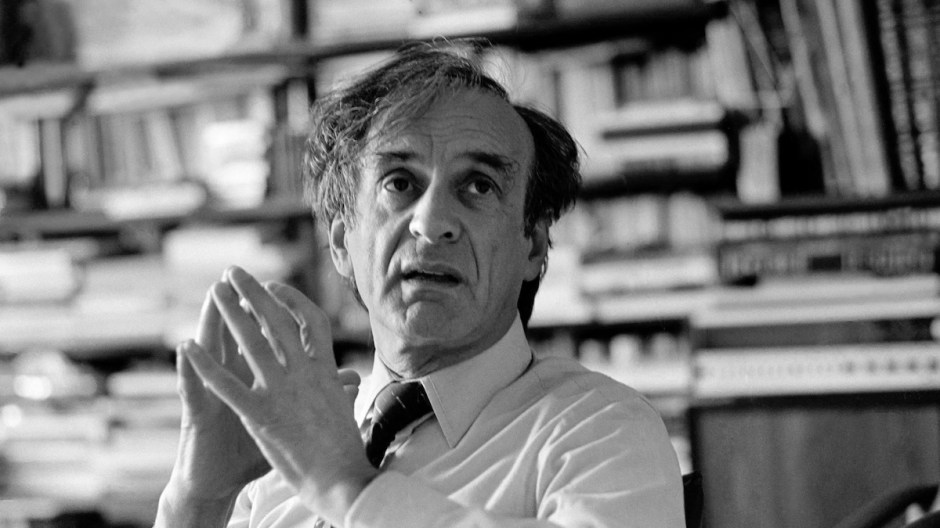

When I was in high school, I read Night by Elie Wiesel. This is the searing autobiographical reflection on Wiesel’s boyhood experience as a Jew living under Nazi Germany: first anti-Jewish laws, then the ghetto, then the cattle car, then the death camp. Wiesel survived where six million other Jews did not, and he dedicated the rest of his life to speaking out against oppression in all its manifestations so that nothing like the Holocaust would ever happen again. In his 1986 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Wiesel says, “I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

Wiesel continues in the speech to call out the oppressive Apartheid regime of South Africa, the crushing of the dissent of Poland’s Solidarity movement, and the plight of the Palestinians in Israel. He says,

“As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our lives will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.”

My prayer to God this year is to live into the truth of Wiesel’s message, which remains just as relevant today as it did when he delivered it 40 years ago. I invite you to live into this truth as well. We must side with the victim, the tormented, the most vulnerable among us, if we are ever to embrace the justice and the freedom that God desires for all people.

Another New Year’s Day song begins with the same sentiment as the one I mentioned at the beginning of this sermon. In their 1983 song, U2 sings:

All is quiet on New Year’s Day.

A world in white gets underway.

I want to be with you, be with you night and day.

Nothing changes on New Year’s Day.

Originally written as a love song for his wife, Bono reshaped the lyrics to make them about Solidarity leader Lech Walesa’s imprisonment and separation from his wife during a long dark winter. Martial law had been in place in Poland since 1981, but dissenters still agitated for change. U2 sings a fervent wish:

We can break through

Though torn in two

We can be one.

Then, before returning to the bleak reality that nothing changes on New Year’s Day, Bono cries out a challenge to himself and to everyone listening to the song: “I will begin again. I will begin again.”

This new year, with God’s help, I will begin again to fight the temptation to check out. I will begin again to confront my discomfort head on in order to stand with the tormented. I will begin again to drink from the fountain of God’s grace so my cup of compassion remains full. Please, join me. Begin again in this new year partnering with God to make all things new.

Banner Image: Elie Wiesel (1928-2016)

- That my exhaustion stems from resisting temptation is a function of my recognized rights. For so many people whose rights are under attack, exhaustion happens as a function of living in bodies that the dominant societal power undervalues or seeks to discard. This second type of exhaustion is existential, whereas mine is circumstantial. ↩︎

So thoughtful and well done Adam! Missing St Marks!